Vignettes from the Hawkbill SS-366Editor's Note: In the fall of 1957, Twin Dolphins Production was producing a television series called, "The Silent Service." These segments were dramatizations of actual submarine experiences. In doing their research, the producers contacted Worth Scanland and Lou Fockele for information about the sinking of the Hatsutaka. This television segment was completed and aired as, "Hawkbill's Revenge." At the end of the show, Captain Scanland was interviewed on television concerning the events just depicted. The information that follows was a response to the producers request for information about the Hawkbill. In a letter dated November 27, 1957 to Admiral Thomas M. Dykers, President, Twin Dolphins Productions, Lou Fockele included the following comments and vignettes: My devotion to Worth Scanland and for Hawkbill makes it easy and obvious to comply with your request of last week for additional material about our war patrols. I conform in my thinking with that of all submariners, I suppose, in the conviction that there is no fighting machine comparable to the submarine. It is a terrible weapon and, at once, a thing of beauty. If there must be war and if men must be killed, surely there can be no more thrilling or impersonal way of killing than this. Hawkbill was a fine ship. None excelled her. And there is no doubt that her excellence was the direct reflection of her superb command office--Worth Scanland. Here was the perfect submarine skipper: bold, adventuresome, daring. He knew his ship and knew his men. He demanded the best of both. He whipped a group--largely landlubbers--into passable sailors, survived their mistakes. our mistakes, more correctly, because I take credit for making the most serious ones I can recall. Worth was cool, calculating, shrewd, and innovator. He had the rare capacity of being the cap'n--absolute and unquestioned--and yet, on occasion, mingling with the hired help without losing or diminishing his authority. Charming, intelligent, aggressive, personable--these are some more words fittingly used in describing him. Now into my meditations: Once, in the Java Sea, I had the deck. Tropical islands were in sight in all directions. The bright lateen sails of inter-island luggers dotted the horizons. It was late afternoon. Remnants of a brilliant sunset remained in the West. The moon was peeping up in the East. The sea was glassy; the breeze was soft and warm. This was a scene right out of a travel poster. The captain came on the bridge, deliberately surveyed this story-book view and said, "And here we are out in this goddam sewer pipe." In Lombok Strait, during our secret anti-patrol boat venture, we took aboard a prisoner. While all these activities were going on topside, I had the diving station at the foot of the ladder from control to the conning tower. When the prisoner came aboard, he was ordered to undress on the bridge, then sent below. I watched his feet appear in the hatch, one bare, one clothed in a white sock. His legs were shaking. Then appeared the rest of him, clothed only in a thin white loincloth sort of thing. At the foot of the ladder, he spied my khakis and saluted. In that we had been instructed to be rough with prisoners in order to improve our intelligence situation, I sternly refused to return the salute. Efforts to move him on, however, failed until I snapped one back and he went on his way. This prisoner, who had nursed a pair of Chevrolet trucks all the way through jungle, across stretches of water, over mountains all the way from Singapore, was within a couple miles of Lombok, his destination, when one of our "cuties" caught his crowd. He was determined to be friendly. And, although the crew had been indoctrinated in his stern handling, it didn't last long. He was shackled to a rough bunk made up in the forward torpedo room. At first, his meager meals were carried to him there. But it was not long until our men were slipping him extra chow, big dishes of ice cream, and plenty of smokes. Thus, as I recall, the captain faced the inevitable and simply had him brought back to the crew's mess for chow, alone, after the watches had gone before. This guy would be handcuffed to a mess table, but when he finished eating, he would swab down the deck, the table, the bench and everything else he could reach in a large circle around him with the handcuff as its center. Where he touched the ship, it sparkled. Later he was given an opportunity to work his magic on the crew's head, which then shone with greater brilliance than it would had several seamen worked on it for a week. After finishing in Lombok, we started on for patrol, encountering one of our boats heading for home. At night, we lay to some yards apart, brought up our prisoner, tied a heaving line around his middle and shoved him over the side. Imagine his thoughts. I was later told that our gentle passenger was turned over to the Aussies in Darwin. He was reportedly blindfolded, met at every turn with a pointed Tommy-gun and whisked away in an armored car. Worth Scanland was a fresh air fiend. As I recall, we transited Makassar Straight at the end of our first patrol without submerging. George Grider, exec., almost had heart failure as Jap planes laced the skies overhead. [Captain Scanland recently told this Webmaster that he had previously served under a sub skipper on the Peto that spent much of his patrol time submerged. Scanland considered that safe but poor policy at best because you would never find a target with such a low level view of the sea.] Back to our prisoner. After capturing him, we made more attacks in Lombok Strait. My station for these attacks was in the forward torpedo room, to which I shifted after the surface phase of the approach was complete. Prisoner was shackled to his empty torpedo-rack bunk. He pretended to be asleep during the approaches, but I was watching him when one fish hit: he rose up from his bunk visibly. But never opened his eyes at all--kept them tightly closed. During one of these night attacks in Lombok, we damaged a PC [patrol craft] which stayed afloat but had no propulsion. Considerably after daylight, the captain toyed with the Japs a bit. Within just spitting distance of the Jap, he would run the periscope several feet out of the water and give us a running account as they brought all their guns to bear and fired frantically. Then he'd down-scope, move to another position and stick it up in the air again. This was great sport. When he finally fired one fish for the coup de grace at close range, he gave us a running account as these guys dived over the side and their ship disintegrated. After our first successful attack, on Hawkbill's first patrol, the target--an auxiliary seaplane tender or something of the sort--lighted up beautifully. Reluctantly, I stood by my TDC [Target Data Computer in the conning tower] while all those fireworks were going on topside, but George Grider saved me by saying: "Lou, Lou, come on up and see this." I needed no urging. Within seconds after I arrived on the bridge, however, our sight-seeing was interrupted by the realization that those graceful streaks lacing over the periscope shears were 20-mm tracers. At this, the captain turned to the bridge speaker and, in injured tones, ordered "all ahead flank. The bastards are shooting at us." Hatsutaka was a real thrill. She was never sighted, but I'd venture to say we knew her course and speed more precisely than her own skipper did. The crippling shots were at rather long range themselves. The fish that delivered the death-blow seemed as if it would never hit -- the time was interminable. The first spread, the one that crippled Hatsutaka, was fired on the surface. I was the fresh engineer officer and as such, was responsible for compensating the boat. After firing these fish on the surface, I was supposed to pump aboard some 12,000 pounds of water to compensate for the weight of fish fired. Instead, I pumped out that amount. As a consequence, when the captain wanted to dive, well after daylight, the ship was too light to go down. We pumped and pumped and pumped before getting enough weight aboard to submerge. I was terribly, terribly ashamed to have so endangered the ship and those aboard her. But the others -- particularly the captain -- did not reject me and I ultimately regained my self-esteem. A lone plane could have given us hell. Two hours on the bottom with that damned Kamakazi overhead constituted a night to remember. Aside from the general discomfort of the situation, I recall standing at the master gyro in the control room, staring blankly at a full-sized section of Sunday funnies from some newspaper. God knows where they came from. But they were soaked with sweat, as if they had been dipped in water. Turning the pages was a chore. Then there was Rex Murphy, the big, bluff mustang with some 11 or 12 patrols under his belt. Murph, stripped to his skivvies and GI shoes unlaced and sloshing (really sloshing) full of sweat walked the ship from fore to aft while the rest of us were trying to shrink up into little invisible, deathly quiet balls. Murph stepped into the control room on one trip and bellowed, "What the hell's the matter, sailors." I virtually fainted. Then there was the Kamakazi's screws, as we lay there on the bottom, everything secured. It was positively petrifying to hear those screws swish-swish-swish- overhead, right through the hull, without benefit of sound gear. His psychological warfare was terrific. That was the night that otherwise strong men who hadn't sweat out all the moisture in their bodies, involuntarily urinated on the deck. Fresh air never was so sweet as upon surfacing following that attack. Then, when it became evident that the captain was determined to get ahead of this guy for another attack, I would have cheerfully transferred to another street car. I was not at all unhappy that we failed to close enough to shoot at this guy again. That was one ship the Japs could keep afloat for all of me. Thus my mingled emotions when we learned, after spending a number of hour in Terampah (?) Harbor, scaring hell out of the Jap garrison and putting the torch to their belonging, that Kamakaze had been dispatched to investigate this invading fleet. But there were no mingled emotions when, only minutes after the captain's intuition told him we'd been there long enough and called all hands back to the ship, we cleared the harbor and were driven down by three enemy planes. What a fix we would have been in had they caught us there. The commander of this cloak-and-dagger crowd we picked up in Brunei for the recco mission, Wild Bill Jinkins was just like Captain Scanland -- a fresh air fiend. Whereas I suppose any other boat in the submarine navy would have stayed submerged for virtually the entire mission, we sat on the surface like a cruise ship and soaked up the scenery. It seemed that the skipper was almost reluctant to interrupt swim call long enough to shell an enemy radio installation or send a mission ashore. When Bill and his crowd went over the side in their fold boats, they were armed to the teeth with all kind of knives, pistols, automatic weapons, grenades and such. On top of this they loaded radar reflectors, infra-red signaling devices and other miscellaneous paraphernalia. I never knew how they managed to squeeze into the little boats. As I recall, one of these men accidentally fired his pistol in the control room as he charged it in preparation for the mission. Don't believe we could ever find where the bullet went into the cork. Christmas 1944, aboard Hawkbill, was festive. We organized a group of carolers, who sang over the intercom on Christmas eve. Some time earlier, we had drawn names for a gift exchange. The ship turned into Santa's toy-shop, with people pecking away in every obscure corner. On Christmas morning, a lookout properly reported "Aircraft on starboard bow." Later, he wasn't so certain it was an aircraft. Then he thought he discerned reindeer and a sleigh and finally Santa's arrival was announced to the company. Then Santa -- a big, fat engineer called Ski in abbreviation of his Polish name -- came down the hatch wearing shorts and a cotton beard. We had accumulated several sea bags full of homemade or accidentally-present gifts. Some sailor had thoughtfully saved a bra in memory of a night ashore and gave it to a chubby motor mech who rather inspired some of the crew. Frenchie, the cook, who was always beating his gums, got a set of tin false teeth. Murph -- who always seemed to have trouble with his dives -- was given a small bucket to use in shifting the bubble from fore to aft. A rank-conscious ensign received an enormous pair of shoulder boards. I was given a broom-stick version of the polished cherry stick to be used in tripping light-house keeper's daughters. Captain Bryand who was Pack Commander or something of the sort and as an extra-numerary was sleeping in the wardroom -- was fixed up by Fred Tucker with a machine to help him sleep when he returned to the beach. It had a red light to simulate the wardroom's night illumination, a tin-can drum containing some beans which simulated the swish of water against the hull as it turned and, among other things I recall, a spare "main drive belt" rubber band and a complete book of instructions. For chow, we dressed, had a special edition of Hawkbill's carbon-paper newspaper, were provided a menu. Watched movies during the afternoon. It was some day. Juel Brown, electrician gives his interpretation of the depth charging by Kamakazi: I was sitting in the crew's mess with the head set on, as that was my station during battle stations torpedo attack. I could hear some of the conversation in the conning tower, also the torpedo fired at the destroyer didn't have time to arm and probably went under him. The next thing I heard was terrific explosions from the depth charges going off, and the Hawkbill taking a fast up angle. It must have been at least 60 degrees. There was a record player sitting on a shelf on the aft side of the galley bulkhead. It was about 5 feet above the deck and it had a one inch rim around the shelf to keep it from sliding off in rough seas. During the attack, that record player did a complete somersault off the shelf and landed along with dishes, cups, silverware and me on the deck next to the forward bulkhead of the crew's quarters. I thought I heard Battle Stations Gun Attack. I picked myself up and rushed to the control room to go up the hatch as I was one of the ammunition handlers for the 5 inch gun. I saw Joe Katnik, the electronic tech. He had one of those burlap garbage sacks full of electronic tubes and was crushing them with a shore patrol night stick. Cork, dust and mercury from the gyro compass was everywhere. The lens from one of the depth gauges was out and lying broken on the deck. Then the Chief of the Boat said, "They have just ordered all back full. We are backing down." A little later he told me and a few others of the gun crew to go to the after torpedo room and wait for new orders. While back there, I looked up at the after room hatch and I could see reddish orange halos around the gasket of the hatch and a shower of water would come down every time those depth charges exploded. Also the Japs had put our some kind of a high pitched siren type noise maker. I believe to confuse our sonic torpedos. Sometime later Ensign Murphy came back and said they wanted about 15 of us to tiptoe to the forward torpedo room as we were getting light in the bow. It was a little tough going in our stocking feet as there was broken glass on the deck everywhere. We spread out a lot of burlap garbage bags to sit on and to absorb our sweat and Doc. Rohr, our pharmacist mate, passed around those 2 oz. bottles of medicinel brandy. After we got out of there and were riding on the surface, I think it was an EM2 named Whitey McLeod and I went down in the after battery well and pumped out all the battery acid in the bilge from the cell that had cracked open during the attack. We isolated that cell by jumpering it out and the after battery was put back online. Juel Brown added in a letter to Lou Fockele: May I take this time to tell you Lou, that Captain Scanland, Fred Tucker and you, Gale Christopher and Eric Schroder were the best officers that I had served under in my 3 1/2 years in the Navy. If you could have taken the Hawkbill to Hell, I wouldn't have hesitated to go with you, because I know you would have gotten us back. I salute you and with great love and admiration proudly say, your shipmate and friend, Juel Serving country, under the sea (Published Veteran's Day 2011)Navy vet John Scott recalls his days as a torpedoman on a sub in the Pacific during World War II. Date published: 11/11/2011 By RUSTY DENNEN With World War II raging in 1943, John Scott was still in high school in Chester, Pa., studying to be a machinist. But he already knew what he wanted to do after graduation--serve on a submarine. "When I turned 17, I made up my mind that I was gonna get in the Navy," said Scott, now 85 and a Fredericksburg resident. Since he was the only son in his family, his mother had to sign to let him go in.

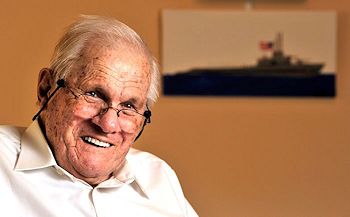

"I guess it's their stealth. You sneak up on somebody and knock them off," he said. At the recruiting office, "The guy there tried to talk me out of it. He said [the enemy] had sunk three of them last week. I said, 'I still want submarines.'" He got his wish. Over the next year, during two patrols aboard the USS Hawkbill in the Pacific, he and his crew were attacked by air and sea, depth-charged and chased relentlessly by sub hunters. Today is the day the nation has set aside to honor veterans such as Scott. As World War II veterans age, the stories of their service are in danger of being lost. Scott shared his war memories in a recent interview at Hughes Home in Fredericksburg, where he lives. After joining up, Scott went to boot camp at Sampson Naval Training Station, N.Y., to Norfolk for torpedoman training, then to New London, Conn. His first glimpse of the Hawkbill was in Fremantle, Australia, where subs from the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia were based. Launched in 1944, the Hawkbill carried a crew of 80, including officers. Actor Spencer Tracy toured the boat during the commissioning ceremony in Wisconsin. It was the first sub named after the large sea turtle. Scott's bunk was next to the No. 1 and No. 2 forward torpedo tubes. When he wasn't tending torpedoes and the boat was on the surface, he was a forward lookout, hunting for enemy ships. "I was checking the water for anything that floated, checking the horizon for anything out there, like [ship] masts, smoke, birds," he recalled. Sea birds signaled the presence of Japanese ships. "They would throw their garbage off the back, and the birds would come around to get the garbage." Enemy planes were always on the lookout for submarines. "They liked to come in low with the sun behind them, and radar didn't pick them up as well," Scott said. If a plane was sighted, the crew had only a minute or two to submerge before bombs were falling. A DEADLY GAME On his first war patrol in 1944 along the Japanese-controlled Lombok strait between the islands of Bali and Lombok in Indonesia, the Hawkbill harassed merchant ships and warships in the South China Sea and the Philippines. After picking up targets on the horizon, the Hawkbill submerged, and a deadly game of cat-and-mouse would commence, Scott said. "You'd figure out the ship's position and make an end run" by going ahead of the convoy to set up a shot. "You'd let him come to you, and then nail him." As a torpedoman, Scott maintained the "fish," as they were called, and prepared them for firing. Technicians would calculate the position and speed of the target, and a "spread" of several torpedoes would be fired. When they hit, "Oh, yeah, you got a bang out of it," he said, the impact unmistakable underwater, even thousands of yards away. "If I happened to be topside, I could see the explosion, and what effect it had on a ship." Four Japanese warships--two destroyers and two sub chasers--were sunk during his time on the Hawkbill, along with some merchant ships and tankers. One night during the boat's fourth patrol, in May 1945, the Hawkbill torpedoed a minelayer in shallow water near the coast of Malaysia. "We submerged and fired two torpedoes. It crippled him. He was dead in the water." The ship fired for hours to keep the Hawkbill at bay as two barges were brought in to shield it from further damage. By dawn, "They anchored him parallel to the beach, so we could get him broadside. Oh, that's a dream." Two more torpedoes, fired over a surrounding minefield, broke the ship in two. The Hawkbill cruised the area as Japanese sailors desperately flailed in the water, looking for life buoys. PRISONER ABOARD Scott said the crew never fired on survivors, and during his time on the boat they took only one prisoner, a scared 18-year-old. The crew gave him clothes, food and other things. "He couldn't speak English, and he'd eat last. We'd fill him up, and when he finished eating, he'd wipe off all the tables, sweep and wash dishes. He loved to see our magazines." Scott worked four hours on, eight off, and four on. "We got to shower twice a week if we wanted it." His bunk area was air conditioned, because of the torpedo equipment. "And we had good food--the best in the Navy." The crew would watch movies in the forward torpedo room. "When we'd run across another [friendly] sub, we'd find out if they had fresh movies and trade them," he said. They would get news and updates about things back home by radio. One of his biggest scares came during a night watch. "We're sailing along peaceful, and out of the corner of my eye, I saw two streaks coming directly at us." The water glowed with phosphorescence; he thought the trails were torpedoes. "I couldn't speak, so I stomped my feet." The boat took corrective action. The wakes turned out to be porpoises. Later, the commanding officer, Lt. Cmdr. F.W. Scanland Jr., called Scott into his quarters to tell him he understood what it meant "to have the hell scared out of you." The Hawkbill sank 16 vessels during the war, and was the first sub to use a new type of homing torpedo that would guide itself to a target. Scott and the Hawkbill made it through the war intact. Many submariners were not so lucky: The United States lost 52 subs and about 3,500 submariners during World War II. PRIDE AND MEMORIES Scott got out of the Navy in September 1945, returning to Chester to become a toolmaker, but that didn't work out. He was on unemployment for a spell, then worked a series of jobs before settling down with his wife, Doris, in Charlottesville, where he worked for Underwriters Laboratories for 15 years.

After retirement, the couple moved to King George County, then to the Ferry Farms neighborhood in Stafford County. His wife passed away a few years ago, and Scott lost his leg due to complications from a medical condition. He lived with his daughter, Tina Critzer, before moving to the assisted-living center in Fredericksburg, where he's receiving hospice care. A black-and-white picture of the Hawkbill hangs on the wall of his room there, along with other wartime mementos. Critzer says her father is proud of his service. "He was always talking about it. I think it was part of his patriotism. That was keenly embedded in us--love of God and love of country." The Rev. Keith Boyette, pastor of Wilderness Community Church in Spotsylvania County, got to know Scott when Boyette was pastor at Fletcher's Chapel in King George, and recently visited him at Hughes Home. "They were among the first people I met. John was very outgoing. He engaged people, was a great talker and he loved to tell stories." He, too, heard Scott's submarine tales. "Going to war, defending the homeland was so important, like the people after 9/11. They had to go; they felt it was a call of honor." The Free Lance-Star Publishing Co. of Fredericksburg, Virginia

|

Why subs?

Why subs?