This is the Captain Speaking

Picture dated January 2000 at the Pensacola NAS Officers Club

|

IN HARM'S WAY - A TRILOGY

PROLOGUE

In November of the year 1778, when the Navy of the American Colonies was in its early days, its most famous officer, Captain John Paul Jones, wrote in part to his French friend, le Rey de Charmont, in Paris, "I wish to have no connection with any ship that does not sail fast, for I intend to go in harm's way. He was making reference to the impending assumption of command of the new frigate Bon Homme Richard, to which he had recently received orders, thus creating an expression which to this day, more than two centuries later, grows ever more popular when wishing to describe the choice of the most bold amongst a list of alternative courses of action. The commanding officer of a submarine in wartime is often faced with such a situation, and the three stories told in this document tell of two that succeeded and one that failed.

FOREWORD

A few words are necessary to describe the general area of the southwestern Pacific region of the war zone during World War Two in which the activities described in these stories took place, as well as the phase of WWII during which they occurred.

To the question of "where", let's start at the Australian port of Fremantle, located on the Indian Ocean near the city of Perth, where were the allied Command Headquarters of the flag officer with the title of Commander Submarine Force Southwest Pacific consisting of submarines of the navies of the U.S., U.K. and the Netherlands.

From Fremantle draw an imaginary line northward along the Australian west coast to Lombok Strait, between the two islands of Bali and Lombok in the Indonesion archipelago. Lombok Strait is the only convenient, deep water passage between the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north, and therefore of vital strategic significance to the Allied submarines based at Fremantle but operating in the South China Sea.

From north of Lombok Strait draw our imaginary line westward to Karamata Strait, between Borneo and Sumatra, and thence into the operating areas of the South China Sea. If we draw our line east to west across the South China Sea from the west coast of the Philippine island of Luzon to the east coast of Indochina, we will have completed our map.

Our stories span the time between the end of December of 1944 and end of WWII in August 1945. From a strategic point of view, this period was one of a fast growing dearth of enemy targets, forcing our submarines to take risks they may have passed up in more lucrative days in earlier months of the war.

THE TRILOGY

STORY #l "TOP SECRET", a tale about spending five hairy days and nights inside the confines of Lombok Strait.

STORY #2 "H.I.J.M.S. KAMIKASI", a tale about taking on (and losing) a battle with His Imperial Japanese Majesty's most skilled anti-submarine destroyer commanding officer.

STORY #3 "H.I.J.M.S. MOMO and FRIEND", a tale about placing oneself on the surface out ahead of two enemy ASW destroyers, sinking them both (a very real "In harm's way" kind of story).

STORY #1

"TOP SECRET"

Our story begins near midnight of New Year's Eve, 1944-45, as a U. S. submarine approached the northern entrance to Lombok Strait on her way to Fremantle to end her second war patrol. Her name was HAWKBILL, and I was privileged to be her commanding officer, often referred to as the "skipper", sometimes as "the Old Man". I much preferred the former, although I was likely called something much worse than "old" when we did something stupid, such as get caught in a very embarrassing situation in Lombok Strait.

A few miles north of the Strait we encountered another U.S. submarine, heading north having just completed an uneventful passage. We hailed her and she stopped nearby so that we could seek her skipper's advice on conditions in the Strait. He said the three known anti-submarine patrol craft were out on the hunt, but well over on the western side of the Strait, so we should stay as close as possible to the eastern (Lombok) side. We thanked him profusely for the helpful information, wished him a successful patrol and put all four main engines on the line just in case.

We entered the northern entrance to the Strait about midnight, hugging the eastern side as close as was prudent. It was close to midnight, a perfectly beautiful night with an absolutely full moon lighting the scene. I was on the bridge, of course, and we were making 18 knots, which should see us through the Strait in less than 30 minutes with the help of the southerly current. I spoke to all hands via the bridge mike, wishing them and HAWKBILL "Happy NEW YEAR".

The words were scarcely out of my mouth when radar (the operator below decks) called up to the bridge, "Radar contact bearing 170", which placed the target ten degrees to the left of our bow. Bad news if it was one of those pesky sub-chasers. During the next three minutes radar reported contacts 20 degrees off our starboard (right) bow and broad on our starboard quarter... we were neatly trapped by the shoreline and three very dangerous enemy vessels,

I will confess to the reader that I was in a quandary... a decision was called for, and immediately. The options were to submerge (but that was not advisable as we would thereby lose the initiative), try to go between number two and number three and pray we'd not be struck by gunfire, which could easily turn us into a surface ship (unable to dive), or just ask God to bring a miracle. This I did, fervently. Dead ahead, perhaps 5,000 yards due south of us, suddenly appeared an often seen tropical phenomenon, a clearly defined, mile or so in diameter, vertical column of rain so dense as to seem solid. HAWKBILL plunged blindly into this heaven sent obscurity. In minutes we were out again, to find all three sub-chasers abaft our beam, and bending on full speed we soon left them far astern.

Other than receiving a salvo from the two 8" artillery pieces which were situated on the southern end of Lombok Island, followed by two more which straddled HAWKBILL, forcing us to seek safety in the depths, the remainder of the journey to Fremantle was uneventful. A few days later the Rottnest Lighthouse rose up on the horizon, and we were soon placing the gangway in place for Rear Admiral Ralph Christie, USN, Commander Allied Submarines Southwest Pacific, to come on board for his "welcome home" visit and briefing. I took the opportunity to describe in detail our adventures in Lombok Strait, sharing with him my forebodings of future serious problems in that troublesome pass. He listened patiently, then took his departure, and HAWKBILL began her two weeks of maintenance. Her officers and crew commenced their well deserved 14 day respite in the lovely city of Perth.

At about 0830 on the 14th and final day of our R & R holiday the phone at the skipper's residence rang. It was the Admiral's aide with the message that, "The boss wishes to see you in his office at 0800 tomorrow morning." There was no offer of an explanation for this unusual request, but of course I gave the proper response and we hung up.

At 0800 next day I knocked on the Admiral's office door at the headquarters in downtown Perth, the aide ushered me in, and I was offered the customary cup of coffee. The aide took his leave and the Admiral opened the conversation by asking me if I would like to be assigned a "special mission" on our upcoming patrol. Thinking this implied the landing or recovery from some small island of one or more Australian coast watchers, as was almost certain to be the case, I responded with a cheery, "We'd be very pleased to do that, sir." I sat back in my chair, and somewhat smugly pleased with myself, began to give thought to the make up of the crew to take the rather risky job of going ashore to make contact with the coast watcher.

Looking me squarely in the eye, RADM Christie said to me, "Worth, I was confident you would accept this mission, and I must now inform you that every word we say to each other throughout the remainder of this conversation is to be classified Top Secret." Recognizing at once that this special mission I was about to learn was certainly not picking up coast watchers, I could only gulp and let out a very weak, "I understand, Sir".

He went on. "We have recently received a small shipment of a new torpedo, the Mark 27 homing torpedo from Newport (the Navy's main torpedo development center located at Newport, Rhode Island). Because it is about half the size of a standard fish, it has been nicknamed 'Cutie'. Your special mission will be to take a load of cuties into Lombok Strait and get rid of those sub-chasers that gave you such a hard time New Year's Eve."

"Because you will be the first submarine to place the Cuties into use against the enemy," he went on, "I'm adding five days to your post-maintenance training workup and a target so you can develop some appropriate tactics to make Cutie work." I know the blood must have drained from my face, but all I could make myself say was a very, very weak, "Aye, aye, Sir", get to my feet and take my leave. How in the world could I find the words to explain to my shipmates the enormous danger of spending time inside Lombok Strait trying to destroy submarine chasers with a weapon not yet ever fired in anger. I expect the question was purely rhetorical, because it had to be done.

What we determined during our five days playing games with our load of exercise versions of the Cuties was that the homing noise detectors, four of them (one on top of the Weapon, one on each side and the fourth under its "chin") were very weak ... so weak that in order to ensure they would pick up the noise of the target's propellers, it was necessary to release them from the torpedo tube only if the launching submarine was directly beneath the target. It takes very little imagination to recognize that placing oneself in a submarine directly beneath a sub-chaser is NOT a healthy tactic, to say the least. But we had our orders, and on our scheduled departure date from Fremantle, we headed north for Lombok Strait.

About midnight a few days later we entered the southern opening to our destination. The first encounter with the enemy was an SD (air search radar) contact, coming directly toward us. When it became obvious we had been detected and the range had closed to about one or two miles, we submerged. Ten minutes or so later, we returned to the surface, to find that "Washing Machine Charlie", as Lou Fockele, our Torpedo Fire Control operator, had dubbed him, was, at least for the moment, ten miles or so away. But not for long. He soon began another approach on us, and again we were forced to dive. We had a problem. If we had to submerged during daylight, and Charlie was on our back all night, we'd never have the essential time to get our electric batteries and high pressure compressed air banks recharged.

The remainder of the night was uneventful. To prepare for our up-coming all day dive, we worked ourselves well north and close inshore, went down to 100 feet and spent a quiet day of inaction, giving all hands as much rest and sleep as possible. As darkness of our second night fell, we surfaced, started the routine battery and air bank charges, and moving to the north entrance to the Strait, stopped the engines and drifted with the current to the south. Sometime around midnight radar made contact on a target and we went to battle stations. Placing ourselves ahead of the target, we slowed to allow him to close range and went down to 200 feet. When the target was right over our conning tower and his screw noise could be loudly heard by us all, I gave the order to launch a "Cutie". We held our breaths. Then "WHAM'... we had our first victim. Pulling off the track to avoid any sinking debris (such as an engine!), we surfaced to see what we had done. Nothing was left of the target, just driftwood. But slowly moving south in the current were two large flat bottom barges, tied to each other as though they had been in tow. Drifting with the current, they and we were soon out of sight of the LOMBOK artillery battery and we closed the barges to see what was inside.

To our amazement, inside each barge were several Chevy pickup trucks and two Japanese soldiers. Made sign signals for them to come aboard, but three of them refused. The fourth came over to HAWIKBILL and jumped to our deck. WE HAD OUR VERY FIRST POW!!! He was immediately dubbed "Willie", stripped to the buff and hustled below. We backed clear and sank the barges with gunfire. What a glorious victory ... surely the way to defeat our enemies was to deprive them of pickup trucks.

Our third night in the Strait began pretty much as had the others until the small hours of the morning when radar reported a contact to the north, seven miles and closing. When the range had sufficiently closed to permit sonar to pick up the prop beats we dove to periscope depth and began the ritual. "Make ready Tube One Forward and Tube Seven Aft". "Conn, keep the bow pointed straight at the target bearing." "Sonar, keep the bearings coming." Soon we could hear the now familiar chunk-chunk-chunk of propellers through the hull, and gave the firing order to the forward torpedo room, "Fire One". Back from the torpedo room came the alarming news, "We think the fish is still in the tube!!". I took that frightening information aboard, the sonarman announced, "Cap'n, I have a second target in the path of the first", and then we could all hear this one too. And now from the forward room, "The fish has just left the tube." I ordered tube seven back in the after torpedo room to be launched, and now we had two of these homing things swimming towards the surface! God forbid they hear one another, I thought, then that wonderful BARR-OOOMM sound came through the hull, and 20 seconds later the second BARR-OOOMM. WE HAD HIT THEM BOTH! Another miracle for HAWKBILL. We immediately pulled clear from beneath the targets and came to periscope depth. As I watched in the dim starlit light there was one sub-chaser lying to with her stern obviously badly damaged, but afloat, all kinds of wreckage and flotsam to mark the spot where the second SC went down, and a lifeboat containing about ten survivors pulling away. Dawn by now being only a short hour away, we stuck around submerged to keep our eyes on SC #l, drifting slowly to the south in the current while firing off a multitude of variously colored rockets.

Dawn broke over the mountainous island of Lombok to our east as approached the wounded SC from that direction. As I looked around the Strait toward Bali I spotted a small motor driven craft leaving the shoreline and heading for the SC. It seemed obvious that if we didn't dispose of her soon, she would be under tow for home base. With that in mind, we made ready one Mk 18 electric standard size fish, setting it to run at zero depth. As we slowly closed the vessel her crew were gallantly fighting back with heavy caliber machine gun fire, but to no avail. When the range closed to 1,000 yards the SC lay broadside to our bow. We fired the first. During the torpedo's one minute run, passing the periscope among those in the conning tower with me, it was fascinating to watch it skimming along just below the surface, enemy sailors scampering about on deck, some jumping over the side. Inexorably ran the fish, until at the end of its appointed run it struck the SC amidships with a mighty thunderous explosion. An extract from the mission report says, "Pieces of the craft, large and small, flew into the air, and in seconds she was no more." The rescue tug turned about and ran for home.

The following 48 hours were spent patrolling Lombok Strait from end to end without a contact, not even Washington Machine Charlie.

Postscript: Ironically, the U.S.S. BULLHEAD, making a northbound transit of LOMBOK STRAIT on the surface on the 6th of August 1945, just days before the end of WWII, was sunk by "Washing Machine Charlie". She thereby gained the dubious distinction of being the last U.S. submarine lost in WWII.

EPILOGUE

In accordance with my instructions at the time of the submission of HAWKBILL'S report of her third war patrol, the section describing our adventures during the five days in Lombok Strait was written up separately, but attached to the full report. I later learned that the "special mission" report was classified at Headquarters as "TOP SECRET", and until the summer of 1998 I had never seen a mention of that account in any document, official or otherwise. In other words, HAWKBILL'S gallant efforts to clear LOMBOK Strait of the enemy has never been acknowledged nor recognized.

STORY #2

"H.I.J.M.S. Kamikazi"

In the early summer of 1945 the submarine U.S.S. HAWKBILL, of which the author was privileged to be Skipper, sailed from Subic Bay in the Philippine Island of Luzon at the beginning of her fifth (and final) war patrol. She was a few miles west of Subic, and about to release her surface escort, when a young electrician's mate came out of the lower deck of an engine room, declaring himself to be a stowaway!! Fred Tucker, our executive officer, wanted to put him aboard our escort for return to the submarine tender where he belonged, but I felt our stowaway had paid HAWKBILL a very high compliment, so I said, 'No, we'll keep him. So inform the tender (from which our new crew member had deserted), and assign him a bunk." (As we'll see, he later must have rued the day he decided to jump ship!).

Several days and six hundred plus miles later we reached our patrol area, which included the Gulf of Siam as well as adjacent waters south along the Malay coast. After several weeks of chasing down and boarding numerous large Chinese rice junks plying back and forth between China and Singapore to feed the thousands of enemy troops down there, we received a highly classified message from our boss, Rear Admiral James Fife, U.S.N., back in Subic Bay. We were informed that a small convoy of several oil tankers, under the protection of a Japanese destroyer named KAMIKAZI, would be enroute from Singapore to Saigon on such and such a date. The message went on to say that the objective of our attack was to be the escorting destroyer! As a veteran of seven war patrols I had never seen (nor heard of) a skipper being ordered to destroy an escort rather then the tankers so vital to the oil starved enemy. What was the significance of this enigma?

Actually, I knew, and the knowledge made me, I'll confess, filled with concern. KAMIKAZI'S skipper was known to his enemies as the most skilled adversary and ASW enemy in the Japanese Navy (and later behaviors substantiated this reputation to a T.) I recall having very, very little enthusiasm for the honor of tackling KAAHKAZI!! But orders are orders, so we closed the coast until we were in 15 fathoms (26 feet between ocean bottom and our keel!!), and waited, stern towards the beach, all bands at battle stations.

At about 1800 local time, an hour or so before dusk, I saw through the high periscope the tips of the masts of a ship approaching from the south. I remember thinking to myself how nice a martini would taste at this juncture... why would anybody in his right mind deliberately place himself and his ship in such a situation? "In Harm's Way", As John Paul Jones once wrote.

As the convoy advanced northward up the coast, with KAMAKAZI steering a sinusoidal course out ahead several hundred yards, we commenced taking radar ranges and visual bearing in order to establish some semblance of a consistent track on which to base a torpedo firing solution. KAMIKASI simply would not provide us with a solvable fire control problem, so the only option was to launch a spread of torpedoes and hope she couldn't dodge them all. When the Torpedo Data Computer (TDC) predicted the target bearing to hopefully give us at least one hit, we launched a spread of three Mark 18 electric fish. (Being electric, the Mark 18, while slower than our steam driven torpedoes, leave no visible wake). When the stop watch indicated the fish were about halfway to the target, I saw through my attack periscope (very small exposure to the target) that KAMIKAZI was running towards us with full right rudder, and in a few more seconds I knew she was threading the spread. I ordered the periscope down and said to the helmsman, "All ahead full, steady as she goes", meaning in seaman's language, LET'S GET TBE BELL OUTA HERE!

After three or four minutes we allowed a bit and I took a quick look at our enemy. All I could see was the bow of KAMIKAZI with "a bone in her teeth", pushing white water to right and left, and sailors on the bow pointing their damn fingers right in my eye!! As a precaution we had loaded a homing torpedo in an after tube, and I fired it in desperation, but by this time the range was too close and fish didn't have time to arm itself. By now KAMIKAZI was passing over our stern, and I pulled down the periscope to keep it from being knocked off. In seconds all hell broke loose as KAMIKAZI dropped a salvo of 17 depth charges (a consensus count we later took), and I'm quite sure no submarine in anybody's navy ever survived such an explosion as HAWKBIILL underwent that fateful moment.

Everyone in the conning tower, including the Skipper, was knocked to his knees. I recall, of all things, that my Naval Academy class ring came off my finger, and I was crawling about trying to find it. The boat was at a sickening up angle, and when I could get to the periscope and raise it, I saw the entire bow of HAWKBILL from the conning tower to the bullnose jutting out of the ocean like a whale coming up for air. Panic might have permeated the boat, but it didn't. The Exec, Fred Tucker, had the presence of mind to call down to the Control Room, to "Flood Negative", and order which opened the vents on the tank which took on seven tons of negative buoyancy forward of the center of buoyancy, thus bringing the bow back down into the water. We came to rest lying horizontally on the bottom, with the top of the periscope shears perhaps 10 to 15 feet below the surface. And an angry destroyer skipper smelling blood.

Cautioning the crew to get comfortable, stay quiet and don't move about to conserve oxygen, I sent Ensign Murphy (Murph to all hands) to go the length of the boat and bring me a report on any significant emergency requirements for action or repair. His report following a stern to stern inspection was both encouraging and worrisome... there was no water entering the boat reported from any compartment. The majority of the observable damage seemed to be centered in and around the galley and crews dining spaces. Broken dishware and glasses everywhere, but certainly to be expected, and certainly not threatening the integrity of the boat. As to machinery, various equipment and such delicate items as the gyro compass, we'd just have to await developments and see what the enemy was going to do. That we soon found out.

After we'd been on the bottom for perhaps twenty minutes KAMIKAZI turned on her active sonar gear and quickly picked up HAWKBILL. As she received the echo off our hull, we could easily hear the pinging frequency increase and soon the sound of her propellers as she passed over the conning tower, then BOOM, BOOM as two depth charges went off very close. The time was now around 1830, half an hour since, our ill--fated (and very ill-executed) attack on KAMIKAZI. She had responsibilities to the tankers of her convoy, and I felt a ray of hope that she would believe she had destroyed us and go away. As she returned for attack number two, my faint hope diminished. I don't recall how many attacks our nemesis made as the horrifying depth charges continued to fall from what seemed like an endless supply while our sense of survival drained slowly away.

After we'd been on the bottom for perhaps twenty minutes KAMIKAZI turned on her active sonar gear and quickly picked up HAWKBILL. As she received the echo off our hull, we could easily hear the pinging frequency increase and soon the sound of her propellers as she passed over the conning tower, then BOOM, BOOM as two depth charges went off very close. The time was now around 1830, half an hour since, our ill--fated (and very ill-executed) attack on KAMIKAZI. She had responsibilities to the tankers of her convoy, and I felt a ray of hope that she would believe she had destroyed us and go away. As she returned for attack number two, my faint hope diminished. I don't recall how many attacks our nemesis made as the horrifying depth charges continued to fall from what seemed like an endless supply while our sense of survival drained slowly away.

Around 2300 (an hour before midnight) someone in the forward battery compartment, site of half our supply of electric energy, passed the word to us in the conning tower that the odor of chlorine gas was apparent. This dreadful piece of information could not have been more serious... chlorine gas, in this case caused by salty sea water seeping into one or more of the 48 large battery cells. Of course chlorine gas is a deadly poison, placing a definite time limit on how long it would be until we were forced to the surface.

While we in the conning tower were trying to find a solution to this latest dilemma we had unintentionally taken our attention away from KAMIKAZFS incessant pinging and the sound of his depth charges. Our sonar operator, in the conning tower with us, reported in a somber voice, "Sir, I believe KAMIKAZI has departed, I can no longer detect her screws and she has ceased pinging." Hope springs eternal in the human breast, and mine was about to burst. I looked at my wrist watch... it was almost precisely midnight. We had been pinned to the bottom of the South China Sea in 15 fathoms of water for almost six agonizing hours and apparently survived... let's see how we are. I stuck my head over the hatch to the Control room below and said, "pass the word through the boat to stand by to surface. I could detect a "quiet cheer" from below, and reached for the diving/surface alarm switch... Ah-Ooga, Ah-Ooga, came the most welcome of all noises, and I felt the high pressure air flow into the main ballast tanks. Soon the air shut off and my eyes went to the depth gage... 90 feet, 80 feet, 70 feet. ON THE SURFACE !!! The helmsman twirled the locking arm on the hatch to the open bridge above and I went quickly up the ladder. As my head reached the level of the bridge deck I threw back my head and looked into a sky filled with ten thousand stars. I confess to shedding a few tears.

We put a main engine on the line to (1) see if it worked all right, and (2) clear the boat of foul air and chlorine fumes. Gradually all hands turned to cleaning the boat up from the effects of depth charges, making tests and inspections of equipment, preparing some food for every body and sending off our report back to headquarters.

Meanwhile I'd decided to catch up with that damn KAMIKAZI and pay off a little debt it seemed we owed her. I asked Fred Tucker, who doubled in spades as navigator on top of his duties as Executive Officer, to provide me with a course and sped to catch KAMIKAZI before daylight, if possible. He did, and we did. By dawn we were out ahead of the convoy and submerged (once more in 15 fathoms of water as the convoy headed across the mouth of the Gulf of Siam.) I mention the water depth again not only because it adds to the risks of attacking KAMIKAZI, but also because I had detected through our one remaining periscope the presence of an aircraft flying ASW figure eights above the convoy.

I had to make a judgment and decision I did not like at all. Given all the factors involved, our quite damaged submarine, the calm sea surface, the aircraft overhead, and the weary state of my crew, was I allowing my personal war with KAMIKAZI to unduly influence my judgment concerning my responsibility for the safety and welfare of my officers and crew. I believed then and believe now over half a century later, that I made the correct decision when I directed that we break off the engagement and start for home base to lick our wounds. I have always known that I lost the battle with KAMIKAZI, but it needs to be pointed out that one will not necessarily come out on top simply by flinging himself "in harm's way", as John Paul might wish us to believe.

(Footnote) In 1969, while lying in a hospital bed, I decided to communicate with the Skipper of KAMIKAZI if I could locate him. At the time my son Tommy was in Japan so I asked him to undertake a bit of research for me. He was able to obtain Commander IC Hara's home address for me and I initiated an enduring friendship with him. An anecdotal piece about him and his idiosyncratic behaviors is appended.

STORY #3

"H.I.J.M.S. Momo And Friend"

The events described in this story took place in the South China Sea during the second war patrol of the United States navy's submarine HAWKBILL, a unit serving under the Allied Commander Submarines Southwest Pacific based at the seaport of Fremantle, Australia. The time frame is late in the year 1944, the venue the South China Sea between the Philippine Island of Luzon and the coast of Indo China. The author was the Commanding Officer (Skipper) of HAWKBILL, with three previous war patrols under his belt.

Our story begins on a beautiful, sunny, calm afternoon as HAWKBILL cruised rather aimlessly on the surface about 60 miles west of Manila, P.I., hoping for some sort of enemy to make its appearance. I was in the wardroom nursing a cup of coffee when the Officer of the Deck on the bridge said on the intercom, "Captain, we have a plane bearing 270 True, range about ten miles, heading for us." "On my way", I said in acknowledgement, and grabbing my binoculars I made my way up the two vertical steel ladders to the bridge.

The O.O.D. pointed to a spot broad on our port beam. Bringing my glasses to my eyes, I immediately identified the aircraft by her enormously high vertical stabilizer as a PB4Y2, a land based U.S. Navy long range reconnaissance plane and a friend. The pilot was steering his place directly at HAWKBILL, and had reduced his attitude to about 200 feet. We had not only begun firing off the colored recognition flares, but radio shack was reporting, "No response" to his repeated attempts to exchange voice contact with our "friend". I couldn't believe what was happening... this idiot was actually making a bombing run on us, and we were a sitting duck!! We brought the boat's "in port" colors on its short staff up to the bridge and began to wave it frantically while I told the O.O.D. to "rig for depth charge", an order which would close all doors and hatches in the boat. As I watched in horror I saw the plane's bomb bay doors open, and I knew we were goners. "What a stupid way to go", I thought to myself

As I mumbled a quick prayer, I watched in utter amazement as the bomb bay doors swung shut and the pilot banked sharply to his right. Almost simultaneously our radio operator shouted up from down below, "I have him on the phone, Skipper. He wants to speak with you". I picked up a headset and mike, and said without introductions, "You blankety blank fool. What the hell are you doing?"

Filled with chagrin and apologies, our pilot friend begged for forgiveness, and personally I was so relieved to be alive that finally I just said to him, "Okay, okay. You are a dummy and we forgive you and next time do your homework. Now tell me ... did you see anything noteworthy out to the west off of us?"

"Well now that you ask, yes we did."

"And what did you see?"

"We saw two enemy destroyers."

"When did you see them?"

"Just minutes before we saw you."

"Did you estimate their course and speed?"

"Course due north, speed fifteen knots."

"Now listen carefully. I want you to fly back to the west, and when you can see both them and us at the same time, get exactly on a line between them and us. When you are there call out 'Mark' to me. I will take a bearing on you and then you can head for the barn. Thanks, and stay clear of friendly submarines."

Everything happened exactly that way, and when it was done we had current position, course and speed of two enemy men-o-war we'd love to take on, or, as J.P. Jones said, "go in harm's way". Bending on four main engines and 18 knots, we headed north.

Four hours later and well after darkness had fallen, we were in position about ten miles dead ahead of our targets, lying to on a calm sea, the sky clear and filled with stars. HAWKBILL was pointed due south towards where we expected our friends to show up soon on the horizon, and we were at battle stations. It was a tingly feeling!

Right on schedule radar reported two targets bearing 180 True (due south), course north, speed fifteen knots. We backed HAWKBIILL slowly, keeping our lowest profile and the bow always pointed directly at the enemy. I could see them clearly through my binoculars from the bridge, but their lookouts and radar operators must have been asleep. They never knew we were there until the torpedoes struck, one in each destroyer.

Subsequent intelligence confirmed the sinkings, and identified our victims as the leader of a class of destroyer escorts named "MOMO" and one of her sister ships. Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the U.S. Navy, later pinned a Navy Cross on the Skipper's tunic to honor HAWKBILL's deed, and I wear it with great pride for every man jack and officer serving with me.

APPENDIX A

About Commander K. Hara

Commanding Officer,

H.I.J.M.S. Kamakazi

Following the almost fatal battle HAWKBILL endured after her attack on KAMAKAZI off the east coast of Malaysia, I vowed to myself that someday in the future I would learn the name of the commanding officer of the latter ship and have some words with him.

When Emperor Hirohito capitulated to the Allies in August, 1945, and after HAWKBILL arrived back home in San Francisco to be placed in mothballs, I found time to write a letter to the Royal (British) Navy Flag Officer in Command at Singapore. I asked that gentleman if he would be so kind as to have a staff officer determine for me the status of the former Japanese navy destroyer KAMAKAZI.

Several weeks later I received a most courteous response signed by a senior staff officer (as one would expect from the very proper Royal Navy). In his letter he related a most intriguing story, which I have the pleasure of sharing with you, the reader.

In accordance with many military customs and traditions, Flag Officer in Command at Singapore had issued orders that Royal Naval officers of suitable rank board each ex-Japanese navy ship in Singapore harbor for the purpose of receiving from each commanding officer his dress sword as a symbol of his personal surrender.

When such an RN officer arrived aboard KAMAKAZI and asked politely For the Captain's sword, Commander K. Hara unbuckled his dress sword from his waist belt and calmly tossed it overboard, where it sank forever into the harbor's muddy bottom. He then took the ship's bugle from the enlisted bugler, blew a short "raspberry" on that horn, and ushered his guest to the gangway. It is said that the Flag Officer in Command was not a little annoyed, but what could he do?

With thousands of Japanese troops now prisoners of war on the small island of Singapore, and food supplies fast becoming a serious problem, returning those troops to their homeland became a task of the highest priority. In order to address this problem, Flag Officer in Command organized a ferrying operation back to the Island Empire, using as his ferries the available ex-enemy ships, including KAMAKAZI.

The reader has probably acquired by now some ideas about the kind of man who lived inside the uniform of Commander K. Hara, Commanding Officer of the ex-Imperial Japanese Navy ship KAMIKAZI, and will understand the feeling of disgust he held at being lowered to the status of a common ferry boat. Commander Hara was aggrieved, angered and outraged.

Just how aggrieved, angered and outraged we shall now see. Having completed his initial journey between Singapore and Sassebo Naval Base on the island of Kyushu with a load of Japan's soldiers, he turned south for the return journey. Passing a stretch of rocky shore on Okinawa Island, he ordered his helmsman to turn to a course due west, ordered the engine room to give him maximum speed, and passed the word, "all hands lay topside". With a hand salute to the Rising Sun colors of Japan's national ensign, Commander Hara rammed KAMIKAZI high and dry on the rocks. He told his officers and men to remove the military insignia from their uniforms and disperse, then individually make their way home. Thus ended the life of a noble ship and the naval career of her noble Skipper.

Several years following the events related in the paragraphs above, my son, Tommy went to Japan on assignment for Dames and Moore, a consulting firm in Los Angeles. During his year-long stay in Japan, I asked Tommy to do a bit of research for me, and locate ex-Navy commander K. Hara.

With his customary acumen and energy Tommy succeeded in locating (now) Mr. K. Hara in his small village in Hosaku Gun, Ishikawa-Ku, Japan. With an address I was at long last finally able to make contact with my friend and enemy, and did so in a long letter. The effect of that letter was simply amazing. When it reached K. Hara's hands he called together all of KAMIKAZI's far flung officers and crew, popped a bottle or more of saki and read to them my letter. He told me that when he read aloud the part wherein I'd told of HAWKBILL's survival from KAMIKAZI's terrible depth charge attack, the assembled KAMIKAZI crew jumped to their feet and gave "a mighty cheer". It was all very touching. Mr. Hara commissioned the painting and framing of a picture of his KAMIKAZI and sent it to me, and we ultimately became quite close friends. Maybe I'll meet him some day.

THE END

APPENDIX B

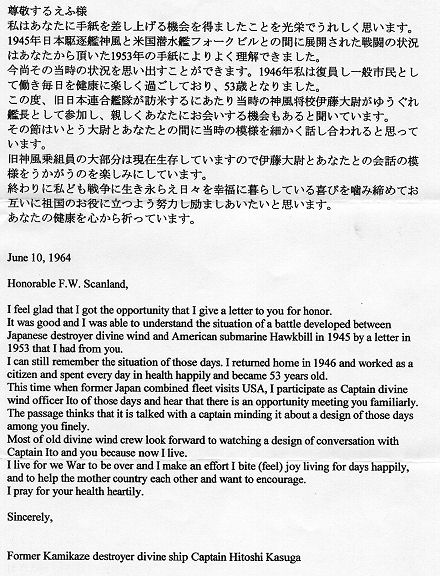

Letter From

Captain Hitoshi Kasuga,

H.I.J.M.S. Kamakazi

This letter was sent to me by Dorothy Scanland in October 2005. The letter speaks for itself but it raises some confusion in my mind as to whom the skipper was during the time of the Kamakazi's attack on Hawkbill. Anyway I include this letter here and will let future historians iron out the discrepancy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Firstly, I must acknowledge the men who made these stories possible, my shipmates and fellow warriors who, with never a whisper of hesitation, followed me into battle. Many of these shipmates had never sailed on, or beneath, salt water, many had never seen it. To them it was the never ending fear of that enemy torpedo which could send us forever to the bottom. I and a few others were aware of "the big picture", aware of the real risks and the odds presented to us. Most just had to trust in their seniors to do the right thing and I was never letdown. I salute you.

Secondly, I must acknowledge the invaluable backup support I received from Lou Fockele, who not only supplied me with copies of HAWKBILL's patrol reports from which I've been able to back up my recollection of events, but kept me honest in recounting them. Lou, old and dear friend, thank you.

Thirdly, I am humbly obligated to my wonderful wife and companion, who has laboriously word by word, sentence after lengthy sentence, paragraph after paragraph concerning stuff about which she knows nothing, such as, "starboard quarter", or "Torpedo data computer". But let me assure our readers, if any, that she has become a whiz on the Dell PC, and I'm considering hiring her out. Dorothy, thank you, dear.

The other day I tried to peddle this manuscript to one of the retired officers' magazines, and was told that nobody was interested in stories about WWII anymore. Well, that's not the point. The point that's important is that I wrote it to keep the memories alive, and to bring a smile and nod of the head to that ever declining small gang of shipmates still left.

Worth Scanland, Captain,

U. S. Navy, (Retired)

THE SECRETARY OF THE NAVY

WASHINGTON

The Secretary of the Navy takes pleasure in commending the

UNITED STATES SHIP HAWKBILL

For service as follows:

"For outstanding heroism in action against enemy Japanese shipping and combatant units during her First War Patrol in the Luzon Straits and South China Sea from September 9 to October 10, 1944; her Second War Patrol from November 15, 1944 to January 5, 1945; her Third War Patrol in the Java and South China Seas from February 4 to April 6, 1945; and her Fourth War Patrol in the Gulf of Siam and South China Sea from May 5 to June 18, 1945. Ferreting out the enemy in dangerously shallow and heavily mined waters, the U.S.S. HAWKBILL launched a series of skillfully executed torpedo and gun attacks and destroyed or extensively damaged sixteen vessels, including two destroyers and a large minelayer, for a total of 40,200 tons. Brilliantly evading numerous depth charges she persistently resurfaced and, holding tenaciously to her targets, quickly maneuvered to strike again with devastating force. She later successfully performed a highly important and hazardous special mission in the narrow confines of Lombok Strait, conducting a series of audacious secret weapon attacks on hostile shallow draft vessels. Despite relentless opposition, the HAWKBILL contributed in large part to the successful blockade of the Indo China coast and toward severing the all important sea lanes between the Empire and her southern conquests, thereby reflecting the highest credit upon herself, her gallant officers and men and upon the United States Naval Service."

All personnel attached to and serving on board the U.S.S. HAWKBILL during the above mentioned periods are hereby authorized to wear the NAVY UNIT COMMENDATION Ribbon.

Signed by the Secretary of the Navy

My Friend

Harry S. Truman

The President Of The

UNITED States of America

In 1946, a little more than half a century ago and before most of my readers were born, I, an ex-submarine skipper from the turbulent days of WWII in the rank of "Commander" (0-5) in the Navy, had recently begun my first tour of shore duty at the Submarine Base then on Key West at the southern tip of Florida. It was my first shore duty in the eleven years since the Academy, and I was milking the assignment for all the pleasures I could arrange.

My duty assignment was as Base "First Lieutenant", a Navy expression which wrapped up all the functions of fire chief, chief of police, keeper of all our vehicles and small boats, and maintainer of peace and quiet. I loved the job and played the part to the hilt.

Into the midst of all this fun came a message from The Secretary of the Navy to our Skipper announcing the arrival of President Harry Truman at our Base, which he had selected for his two weeks winter vacation. As one can imagine, we went straight to "battle stations". "All hands and the ships cook," as we say, and even the officer's wives were placed in charge of readying the new LITTLE WHITE HOUSE. When the President and his entourage arrived on board, every piece of silverware sparkled and every piece of china gleamed, we were very proud of our effort at Navy hospitality.

On the morning following the arrival of our guests, I was dressed in tropical whites, standing at the picket gate separating my front yard from the sidewalk, when I spotted Mr. Truman striding briskly along the sidewalk toward me, his escort of Secret Service men trying desperately to keep up. Not knowing what else to do, I snapped to attention and gave the President a fine salute, saying " Good morning Mr. President". Mr. Truman stopped in his tracks, turned to face me, returned my salute, and said "Good morning to you too. May I inquire as to your name?" "Of course Sir, I am Commander Worth Scanland, US Navy, at your service, Sir." "Well, Commander Worth, it's such a beautiful day, why don't you join me while you tell me what this Base does and why?" Half an hour and a good mile later he dropped off as we passed by The Little White House, saying, " I enjoyed our conversation. I'll be at your gate tomorrow same time." Considering that as an order, I simply saluted and responded, "Aye, aye, Sir," and took my departure. We had that walk together every morning of his ten more days as our guest, becoming real friends in the process.

A day or so later, one of the President's staff came to me, with the request that I arrange a fishing trip at sea, so the press (present, of course, in large numbers) could have a photo opportunity to show the President's inland admirers that he really was a fisherman. I visited most of the bars along Main Street until I located "Charlie", Key West's veteran home grown fishing expert, and hired him for the day to make absolutely damn sure that Mr. Truman caught a bona fide ocean fish. The press boat had a picnic. Mr. Truman hooked a twelve-pound grouper, and with a little help from me and the cheers from the press boat, he managed somehow to bring him to gaff. I wouldn't be so bold as to say the President enjoyed the experience, but he was a good sport and smiled for his constituency who would see him at home on Pathe news.

In the good old days of dignified presidents and respectful citizens, the country maintained for the Presidents personal use, a beautiful steam driven yacht named WILLIAMSBURG. She had originally been the property of a wealthy family named Flieshman, who had generously donated her to the Navy, which maintained and manned her. Of course, her home port was the Navy Yard At Washington, D.C., and so Mr. Truman gave directions for Bess, as everyone knew Mrs. Truman, to embark in the yacht and ride her to Key West. There the Trumans held marvelous dinner party for twenty Key West military and civilian guests, the Scanlands included.

Those were the Very, Very, good old days.

Worth Scanland,

Captain, U.S. Navy (Retired)

Hawkbill Reunion at King's Bay

6 November 2000

Let me tell you of a journey back into history fifty five long years ago. Every year since the end of World War II, veterans of that war, at least U.S. Navy veterans, have met in various cities about the nation to reminisce over their shared experiences together.

By personal bias I am not an habitual devote' of groups of people, preferring small (like 8 for dinner) groups, where intelligent conversation is possible and likely to occur. But gathering together the remnants of a relatively small (such as 22 in the case at hand) is not only a happy occasion, but an emotional occasion such as one may never before have experienced,

The crew of a U.S. submarine such as those which fought and won the war with Japan in 1941-45 averaged about 70 officers and enlisted men. These men, from top to bottom, were all volunteers, very well trained, highly skilled, totally motivated and in general extremely loyal to their skipper (commanding officer) and "Boat", as submariners call their vessels. What Dorothy and I experienced November 3rd at the reunion of the submarine crew of U.S.S. HAWKBILL (SS 366) was so remarkable (besides being only our second such experience), as to remain the happiest event of its kind in my life, but certainly one to cherish.

The HAWKBILL reunion this year was held over a period of five days, but we saved our attendance until the final day. Many other boats were represented at this event, each holding its own gathering. On the last day Dorothy and I appeared at the meeting place, a sort of rustic country-like restaurant. As she helped me and my cane enter the meeting room all hand jumped to their feet and gave us a rousing welcome. I was overcome. One by one they came to me and throwing their arms around me, gave me such hugs that I almost smothered. Many of these seasoned warriors were openly weeping, as was I. This must have gone on for 30 minutes, by which I was exhausted. The emotional charge in that room could have driven one of HAWKBILL's 1600 horsepower dynamos. Nothing to compare with it could ever happen again, and I am feeling an open heartfelt love which has forever changed whatever remains of my unworthy life.

I don't believe I've mentioned the location of the reunion. On the southeastern Atlantic coast of Georgia, just above the Georgia-Florida boundary line, is located a vitally significant nuclear powered ballistic missile submarine base, called KING'S BAY. At this home port are based a squadron of ten or twelve submarines which displace 17,000 tons (HAWKBILL displaced 2,300 tons by comparison). Each of these monsters is armed with 24 triple one megaton warheads, so sleep in peace ...Worth's contribution to the national defense is keeping the peace. Lots of love from our house to yours.

Unluckiest Submarine

MID-AUGUST

There is something mysterious about mid-August which seems to haunt the Navy..., something awesome and spooky..., something to cause us to pause and reflect. This "thing" is a proclivity towards or tendency to suffer unhappy events. An example or so might be in order.

In mid-August 1941 at the launching of the newly commissioned submarine SEADRAGON at Groton, Connecticut, the vessel slid five feet down the ways and inexplicably came to a stop. She made it the rest of the way a week later, but was a bedeviled craft the rest of her life.

In mid-August of 1942 SEADRAGON arrived in Manila. P.I. just in time to "attend" the Army-Navy football game, which Navy lost shamefully,

In mid-August 1943 SEADRAGON took a Japanese air-dropped bomb down her open conning tower hatch, killing her junior officer.

In mid-August 1944 SEADRAGON suffered the experience of her leading quartermaster coming down with acute appendicitis-the pharmacist's mate removed the infected organ without anesthesia on the wardroom table.

In mid-August 1945 SEADRAGON swung around her hook in Bruni Bay, Borneo, while the rest of the Navy celebrated Armistice Day on the way home to San Francisco.

In mid-August 1946 SEADRAGON was placed out of commission at Mare Island Naval Shipyard, proclaiming herself to be the unluckiest submarine in the Fleet. Who am I to argue? She was certainly the unluckiest submarine I ever served aboard!!!! Surely I didn't have anything to do with that either.

Worth Scanland,

Captain, U.S. Navy (Ret.)

Watching the Army-Navy Game in The Good Old Days

by Worth Scanland

When the Saturday of the Army and Navy football classic finally rolls around, the fans and Alumni either are lucky enough to be in the stadium, or comfortably seated in front of a color television almost anywhere on the plant. Not so in the mid-'30s in the Asiatic fleet, as was I for the games of 1937 and 1938. Let me tell you about it.

Try to imagine a world where there were no direct communications beyond the boundaries of CONUS, except for radio signals using Morse Code, generated by devices called "speedkeys," driven by radiomen, all through a network of radio towers which could talk to each other. For example, a telephone line could carry a Morse Coded signal from the football stadium to the tower at NAA Annapolis, which then re-sent it to a similar tower in San Francisco, which in turn would transmit it (by hand, mind you) to Pearl Harbor, then on to Guam, who sent it to Radio Cavite at the Naval Air Station on Manila Bay. At long last the message reached the ear phone of two young officers, one Army and the other Navy.

These two people were about as busy as a one-armed paper hanger with the hives. Back at the stadium an announcer would speak into a phone. "Army's ball, first and ten on Navy's 30 yard line." At Radio NAA in Annapolis a radioman would transmit that statement to Radio San Francisco, who would, in turn, relay it to Radio Pearl, and so on, until it reached the ear phones of the two guys in Manila, who were, I should tell you, on a platform in the main ballroom of the Army and Navy Club on the shores of Manila Bay.

The Army and Navy Club was a privately owned and operated social establishment with membership limited to U.S. military officers and their wives, plus a few special guest members, such as diplomats and employees of the High Commissioner's office. Dues were modest and ladies were prohibited from entering the men's bar. It was the social center for U.S. military officers and a stop there for a toddy on the way home at the end of the workday was SOP. There were two tennis courts, a swimming pool, and the best swing band west of Benny Goodman.

Because of the time zone differences, the Army and Navy football game started at 1:00AM Manila time, so the routing was to go to bed real early the evening before the game, then arise about midnight, shower and dress in uniform whites, the girls in long skirts, and assemble in the ballroom of the Club where chairs were set up, and order a drink to get in the proper spirit of "Beat Army."

In order to follow the game as it progressed, a roughly ten-foot long, six-foot high plywood backboard with a football gridiron painted on it, was erected. It was coated with some sort of stickum, so that a flat, oblate, spheroid, mock football could be moved back and forth on the gridiron by the operators as the game progressed. It was a great idea, and from kick-off to the final whistle, we were spellbound by the game which ended about daybreak with the Army fans throwing the Navy wives into the pool, long skirts and all, because in 1937 Navy lost 0 to 7, and in 1938 we again lost, 7 to 14 as I recall. But we sure had a great time.

|