- STORIES -

These are a few of the over 70 paintings memorializing the role of black Americans in aviation. Stan Stokes is working on a project to produce a coffee-table style book containing these paintings and stories.

Bessie ColemanBessie Coleman, the first black to earn and receive a pilot’s license. In 1921, Bessie went to France where she learned to fly and received a French pilot’s license that the US had to honor when she returned. Her aviation career ended tragically in 1926 She died while riding in the passenger seat of her "Jenny" airplane. Her mechanic William Wills was piloting the aircraft when it suddenly dropped into a steep nosedive and then flipped over and catapulted her to her death. After her death, Bessie Coleman Aero Clubs suddenly sprang up throughout the country. In 1931, a group of black pilots established an annual flyover of Coleman's grave in Lincoln Cemetery in Chicago. Despite her relatively short career, Bessie Coleman strongly challenged early 20th century stereotypes about white supremacy and the inabilities of women. By becoming the first licensed black female pilot, and performing throughout the country, Coleman proved that people did not have to be shackled by their gender or the color of their skin in order to challenge their dreams. |

Eugene BullardBorn in a three-room house in Columbus, GA. 1895, Eugene James (Jacques) Bullard was the seventh child of Josephine Thomas and William O. Bullard. He was to become the world's first black combat aviator. At the beginning of World War I, Bullard joined the French army, serving in the Moroccan Division of the 170th Infantry Regiment. The French government awarded him the Croix de Guerre for his bravery at the Battle of Verdun. Twice wounded and declared unfit for infantry service, he requested assignment to flight training. He amassed a distinguished record in the air, flying twenty missions and downing at least one German plane. |

Bob WilliamsBob Williams - 100th Fighter Squadron, Flying P-51D shot down 2 Focke Wulfs. He wrote the screen play that became the HBO movie "The Tuskegee Airmen". Bob Williams labored for more than four decades trying to persuade film and TV producers to record his story of the small group of black men who served their country despite entrenched racial discrimination. Finally, in 1995, HBO produced the film which starred Laurence Fishburne, Cuba Gooding Jr. and Andre Braugher. Fishburne played Hannibal Lee, a character loosely based on Williams. The film earned three Emmy Awards, a Peabody, a Cable Ace Award and two NAACP Image Awards. It detailed how the "Fighting 99th"--the first squadron of black combat fighter pilots and the vanguard of nearly 1,000 black fliers--overcame racism for the right to serve their country, and emerged from the war wreathed with honor but with little public acclaim. |

Charles Bailey

Charles Bailey was the first black aviator from Florida to become a Tuskegee Airman. He is credited with two aerial victories, a Focke-Wulf-190 in “Josephine,” a P-40 Warhawk named for his mother, and later a Messerschmitt Me 109 in “My Buddy,” a P-51 Mustang named for his father. Bailey scored these victories while covering the allied amphibious landings at Anzio, Italy. The Fighting 99th converted to the P-51 in July 1944. Ten days after checking out in the new fighter Lt. Bailey splashed the FW 190. On July 18, 1944 the 99th Fighter Squadron flew its second combat mission as part of the 15th Air Force. During that mission the Red Tails of the 332nd FG knocked down Twelve enemy fighters. Capt. Edward L. Toppins and Lt. Charles P. Bailey were the only pilots from the 99th to score victories that day destroying one Focke Wulf fighter apiece. Lt. Bailey flew a total of 133 missions and received the Air Medal with four Oak Leaf Clusters and was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross on May 12, 1945. |

Eleanor RooseveltApril 19, 1941 - Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt visited Tuskegee and met Charles "Chief" Anderson, the head of the program, Mrs. Roosevelt asked, "Can Negroes really fly airplanes?" He replied: "Certainly we can; as a matter of fact, would you like to take an airplane ride?" Over the objections of her Secret Service agents, Mrs. Roosevelt accepted. The agent called President Roosevelt, who replied, "Well, if she wants to do it, there's nothing we can do to stop her." With Mrs. Roosevelt in the back seat of his Piper J-3 Cub, Chief Anderson took off and flew her around for half an hour. Upon landing, Mrs. Roosevelt turned to the Chief and said, "I guess Negroes can fly," and they posed together for a historic photo. Not long after Mrs. Roosevelt's return to Washington, it was announced that the first Negro Air Corps pilots would be trained at Tuskegee Institute. |

Benjamin O Davis JrDavis attended the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1932. During the entire four years of his Academy term, Davis was shunned by his classmates, few of whom spoke to him outside the line of duty. He never had a roommate. He ate by himself. His classmates hoped that this would drive him out of the Academy. The "silent treatment" had the opposite effect. It made Davis more determined to graduate which he did 35th in a class of 278. In World War II, Davis was commander of the 99th Fighter Squadron and the 332nd Fighter Group. Davis himself flew sixty missions in P-39, P-40, P-47 and P-51 fighters. As commander of the 332nd, between missions, Davis returned to address congressional committees to keep the Tuskegee program alive. There were many congressmen who wanted to see the program fade away but through Davis' efforts, the program survived to become one of the most celebrated groups in that war. After the war, Davis remained in the Air Force reaching the rank of Lieutenant General in 1965. He retired from active military service on February 1, 1970. On December 9, 1998, Davis was advanced to the rank of General, U.S. Air Force (Retired), with President Clinton pinning on his four-star insignia. Davis passed away on July 4, 2002. A Red Tail P-51 Mustang flew overhead during his Arlington funeral services. President Clinton said, "General Davis is here today as proof that a person can overcome adversity and discrimination, achieve great things, turn skeptics into believers; and through example and perseverance, one person can bring truly extraordinary change." |

Mac RossFrom Dayton, Ohio, Mac Ross was the youngest of the first five graduates of the Tuskegee air cadets. Captain Benjamin O. Davis, 2nd Lieutenant Lemuel R. Custis, 2nd Lieutenant Charles DeBow, 2nd Lieutenant George S. Roberts, and 2nd Lieutenant Mac Ross became the first of 994 pilots who would graduate from the segregated Tuskegee Army Flying School over the following four years. The Tuskegee Airmen were the first African-American military aviators in the United States Armed Forces. During World War II, black Americans in many states were still subject to the Jim Crow laws and the American military was racially segregated, as was much of the federal government. The Tuskegee Airmen were subjected to racial discrimination, both within and outside the army. All black military pilots trained at Moton Field, the Tuskegee Army Air Field, and were educated at Tuskegee University, located near Tuskegee, Alabama. Before the Tuskegee Airmen, no African American had been a U.S. military pilot. In 1917, African-American men had tried to become aerial observers, but were rejected. African American Eugene Bullard served in the French air service during World War I, because he was not allowed to serve in an American unit. Instead, Bullard returned to infantry duty with the French. |

Roscoe BrownRoscoe C. Brown, Jr. is one of the Tuskegee Airmen and former squadron commander of the 100th Fighter Squadron of the 332nd Fighter Group. He graduated from the Tuskegee Flight School on March 12, 1944 as member of class 44-C-SE and served in the U.S. Army Air Forces in Europe during World War II. “I come from a generation of African-Americans where we were always trying to be better. We were taught that you had to be better than whites in order to move ahead, so we were very competitive. I went to the most competitive high school in the country for blacks--Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C.--and we developed the first black federal judge. In addition to our academic work, we were very competitive athletically. I was one of the first blacks to play lacrosse; I played football and basketball so I was accustomed to competition. Practically everyone in the Tuskegee Airmen was an exceptional scholar and athlete, so the competition was really great and it helped to bond us together." |

Roscoe Brown in BunnieRoscoe Brown flying his P-51, Bunnie, over Italy. "High-altitude escort was probably the most important plane in the war and shortened the war by about six months because it enabled the bombers to go a longer distance into Germany and destroy their infrastructure—their rail hubs, oil refineries, and so on." "As a result, we did not shoot down many planes, although on the longest mission of the 15th Air Force, from southern Italy to Berlin, we shot down the first jet planes in the 15th Air Force—the German Me-262—and I was the one who shot down the first of those jets. It was the first plane I’d shot down before. We used a maneuver that we’d been practicing, where when the jets were coming up, instead of going right after the jets so they could get away from us, cause they were faster, I went down under the bombers away from the jets, made a hard right turn so I could put the jet into my gun sight, and boom. It was a good maneuver because the jets were faster than we were, but we were more maneuverable." |

Rusty BurnsRusty Burns sitting in his P-47 Thunderbolt. Rusty was in the 99th Fighter Squadron when they where flying Thunderbolts. He successfully completed his training in September of 1944 and became a member of the 99th Fighter Squadron at Godman’s Field in Kentucky. Burns’ military career ended in June of 1945 as World War II ended. He returned to Los Angeles and ultimately returned to aviation after buying and rebuilding his own airplane. In 1955, he opened Rusty’s Flying Service and began giving flight instruction, at Compton Airport. He trained over five hundred students before selling his business in 1971. |

Erwin LawrenceErwin Lawrence climbing from his P-51. One of the original pilots with the 99th Fighter Squadron to see combat, he became CO of the 99th. One of the first Tuskegee graduates, Capt. Erwin B. Lawrence Jr. eventually led the 99th Fighter Squadron for six months. Lawrence of Cleveland graduated from flight training on July 3, 1942, at Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama. Lawrence joined the 99th Fighter Squadron, which was declared combat-ready on Sept. 15. The squadron finally deployed in April 1943, serving first in North Africa then moving to Italy in July. Lawrence led several escort missions in the following months. On Oct. 4, he led 37 P-51 Mustangs on a strafing mission at a Greek airfield at Tatoi. As Lawrence's plane approached the target, "suddenly it flipped into a spin," 1st Lt. Leonard M. Jackson wrote in a military report. "After about two or three turns, the plane crashed into the ground and exploded into flames." |

Clarence "Lucky" LesterClarence "Lucky" Lester standing on his P-51. Born in Richmond, Virginia in February 1923, he grew up in Chicago and went to college at Virginia State where he was a football star, but when WWII broke out he was accepted in the Army Air Corps and and went down to Tuskegee for training. After graduating in 1943 he was assigned to the 100th fighter squadron. He flew ninety combat missions. A skilled pilot he was called "Lucky" by his buddies because (among other things) his plane remained undamaged even when he shot-down three enemy planes - in less than five minutes - on July 18, 1944. Lester remained on active duty, with the U.S. Air Force, for 28 years. He died in March of 1986 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. |

George "Spanky" RobertsGeorge S. “Spanky” Roberts was among the first African-Americans selected for pilot training at the famed Tuskegee Army Airfield. He commanded the 99th Fighter Squadron and the 332nd Fighter Group, which saw action over North Africa and Italy. After President Harry S. Truman desegregated the armed forces for good in 1948, Roberts became the first African American officer to command a racially-mixed unit at Langley Air Force Base. Roberts returned to combat in Korea, commanding the 51st Air Base Group and the Air Force base at Suwon. He retired from the Air Force in 1968. |

99th Fighter SquadronPilots of the 99th Fighter Squadron, the first to get into combat. Standing in front of one of their P-40Fs are Herman Lawson, Spann Watson, Robert Deiz, and Charles Dryden. The 99th was originally formed as the Army Air Force's first African American fighter squadron, then known the 99th Pursuit Squadron. The personnel received their initial flight training at Tuskegee, Alabama earning them the nickname Tuskegee Airmen. The squadron was originally tentatively scheduled to fly air defense over Liberia but was diverted to the Mediterranean Theater of Operations. May 31, 1943: the 99th Fighter Squadron arrived at Farjouna in Tunisia, attached to the 33rd Fighter Group, flying P-40s. Three days later, Lt. William A. Campbell, Charles B. Hall, Clarence C. Jamison and James R. Wiley, flew the squadron's first mission, a 'milk run' over Pantelleria. On June 9, six pilots of the 99th FS became the first U.S. black pilots to engage in aerial combat. Led by Lt. Charles Dryden, Lt. Willie Ashley, Sidney P. Brooks, Lee Rayford, Leon Roberts and Spann Watson, exchanged fire with German fighter planes, with no losses to either side. The Italian garrison on Pantelleria surrendered on June 11, 1943, in large part due to the powerful air attacks it had been subjected to. The 99th was a key part of the air assault. The Tuskegee Airmen continued flying and fighting, killing and dying, until the end of the war in Europe in May, 1945. |

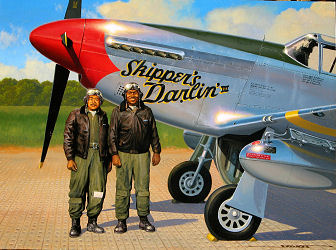

Turner & BriggsAndrew "Jug" Turner and John Briggs - Both flying P-51Cs with the 100th Fighter Squadron, Turner became the CO of the 100th. The 100th Fighter Squadron was established in February 1942 at Tuskegee Army Airfield, Alabama to train African-American flight cadets graduated from the Tuskegee Institute Army contract flying school. At Tuskegee, the squadron performed advanced combat flying training. As the number of graduated from the Tuskegee school grew, two additional squadrons the 301st and 302d Fighter Squadrons were activated at Tuskegee Army Airfield, forming the 332d Fighter Group. |

Charles McGeeMcGee was born in Cleveland, Ohio on December 7, 1919. He enlisted in the US Army on October 26, 1942 and became a part of the Tuskegee Airmen having earned his pilot's wings, and graduating from Class 43-F on June 30, 1943. By February 1944, McGee was stationed in Italy with the 302nd Fighter Squadron of the 332d Fighter Group, flying his first mission on February 14. McGee flew the Bell P-39 Airacobra, Republic P-47 Thunderbolt and North American P-51 Mustang fighter aircraft, escorting Consolidated B-24 Liberator and Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers over Germany, Austria and the Balkans. During missions, he also engaged in low level attacks over enemy airfields and rail yards. On August 23, 1944, McGee while escorting B-17s over Czechoslovakia, he engaged a formation of Luftwaffe fighters and downed a Focke Wulf Fw 190. Promoted to Captain, McGee had flown a total of 137 combat missions, and had returned to the United States on December 1, 1944, to become an instructor on the North American B-25 Mitchell bombers that another unit of the Tuskegee Airmen were working up. He remained at Tuskegee Army Air Field until 1946, when the base was closed. When the Korean War broke out, he flew P-51 Mustangs and then Lockheed F-80 Shooting Stars and Northrop F-89 Scorpion aircraft. During the Vietnam war, as a Lt. Colonel, McGee flew 172 combat missions in a McDonnell RF-4 photo-reconnaissance aircraft and also RF-4C Phantom II jet aircraft. McGee continued to serve in the Air Force for 30 years until his retirement in 1973. In this active service career, he achieved the highest three-war fighter mission total, 409 fighter combat missions, of any Air Force aviator. |

Clarence JamisonClarence C. “Jamie” Jamison trained at the Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama during the war for duty in the then-segregated U.S. military forces. He flew a fighter on 67 combat missions in the 99th Pursuit Squadron, seeing action in North Africa and Italy. During one mission over Anzio, Italy, Jamison’s squadron encountered an enemy formation that outnumbered them, but the “Black Eagles," as they were called, shot down five German planes. Jamison once recalled that battle for a newspaper reporter, remembering when the aerial dogfight brought his fighter right above an enemy plane: “The pilot looks at me. I look at him. We’re both surprised to be so close. I fire and he starts smokin’.” Jamison also once remarked on the two battles that he and fellow Tuskegee airmen faced – fighting both the enemy and racism – “The flying was enough of a challenge in itself. We didn’t have time to worry about what Mr. Charlie (whites) thought. We lived in a racist society. I didn’t go in expecting the Air Force to welcome me with open arms.” When the Tuskegee Airmen were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2007, Jamison wryly observed, “It’s a nice honor, but it’s a little late.” After the war, Jamison served in the Air Force as an accounting and finance officer, retiring in 1963 after 22 years of service. |

Alex JeffersonAlex Jefferson was born in Detroit, Michigan and graduated from high school in 1938. In 1942, he graduated from Clark College in Atlanta with a Science degree in Chemistry and Biology. Called up for flight training in April 1943, Jefferson received orders to report to Tuskegee Army Air Field to begin flight training. Receiving his pilots wings and officers commission at Tuskegee, he was assigned to the 332rd "Red Tail" Fighter group at the Ramitelli Airfield near Foggia, Italy, flying the P-51 Mustang. Assigned to a fighter escort wing protecting bombing missions of the US 15th Air Force, his job was to attack key ground targets and guard the bombing mission against Luftwaffe fighters. During his 19th mission over Toulon, southern France on August 12, 1944 he was shot down. Parachuting to safety, he was captured by Nazi ground troops and was sent to POW camp Stalag Luft III in Poland. He was later repatriated by Patton's 3rd Army on April 29, 1945. In 1947 Jefferson received his teaching certificate from Wayne State University and began teaching elementary school science for the Detroit Public School System. He received his M.A. degree in education in 1954. In 1995, Jefferson was enshrined in the Michigan Aviation Hall of Fame. In 2001 he was awarded the Purple Heart and in 2007, the Congressional Gold Medal. |

Roscoe Brown & Lee ArcherOn the left, Roscoe C. Brown, Jr., born March 9, 1922 in Washington, D.C. is one of the Tuskegee Airmen and former squadron commander of the 100th Fighter Squadron of the 332nd Fighter Group. He graduated from the Tuskegee Flight School on March 12, 1944 as member of class 44-C-SE and served in the U.S. Army Air Forces in Europe during World War II. During this period, Captain Brown shot down an advanced German Me-262 jet fighter and an FW-190 fighter. After the war, Captain Brown resumed his education. His doctoral dissertation was on exercise physiology and he became a professor at New York University and President of Bronx Community College. In 1992, Brown received an honorary doctor of humanics degree from alma mater Springfield College. On March 29, 2007, where he was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in recognition of their service. Dr Brown is currently a professor of Urban Education at the City University of New York Graduate Center. On the right, Lee Andrew Archer, Jr. was born in Yonkers, New York, September 6, 1919. He grew up in New York's Harlem district, later attending New York University. Upon graduation, he joined the Army in the hopes of becoming a pilot. At that time, the Army did not accept black pilots, so Archer was posted to a communications job as a telegrapher and field network-communications specialist in Georgia. When the Army's policy changed, he was accepted to the training program for black aviators at Tuskegee Army Airfield in Alabama, graduating first in his class. He was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant on July 28, 1943 and later earned the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. During World War II, Archer flew 169 combat missions, including bomber escort, reconnaissance and ground attack and is officially credited with 4.5 enemy fighter aircraft shot down. Archer passed away in New York City on January 27, 2010 at age 90. |

Wendell Pruitt & Gwynne PiersonThe 332nd Fighter Group, the famous Red Tails, spent two months in combat flying the P-47 Thunderbolt before they moved to the P-51 Mustang. In June, 1944, heading home after a mission, their flight path took them across the Adriatic Sea and close to Trieste Harbor. A war ship, destroyer TA-23, was sighted and was flying the German Naval flag. The 332nd P-47s were low on fuel and only had machine guns, no bombs. The ship opened up on them with its anti-aircraft guns and the P-47s opened up with their 50 caliber machine guns. The first of the P-47s attacked without results. Next up were Capt. Wendell Pruitt and Lt. Gwynne Pierson. Pruitt made some good hits that set the ship afire. Then, Pierson's bullets started to impact the ship. Whether it was the fire started by Pruitt or by Pierson's bullets hitting an ammo magazine, the ship was suddenly ripped apart by a massive explosion. Despite the impact of the explosion, and jagged holes made by shrapnel hitting the plane, Pierson's P-47 got him home. This was the only enemy ship to be sunk with machine gun fire alone during WWII. For this action, Capt. Pruitt and Lt. Pierson were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. Wendell Pruitt, native os St. Louis, Missouri, flew 70 combat missions overseas. In addition to the German destroyer, he is credited with shooting down three enemy planes in the air, and destroying several others on the ground. His air victories earned him the rank of captain as well as several awards and honors, including the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal with six Oak Leaf Clusters. He was killed during a training exercise in 1945. Unfortunately little information exists for Lt. Gwynne Pierson. Should you have a biography on Gwynne, please notify this Webmaster at dickcl (at) yahoo.com. |

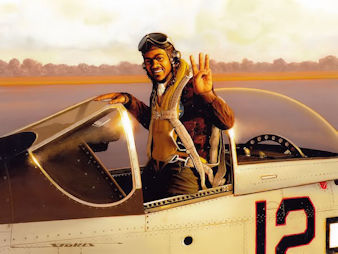

Harry StewartAfter joining the Air Force at age 18, Harry Stewart ultimately was assigned to train with the Tuskegee Airmen. When in combat, he managed three kills over the Italian countryside in one day. The first two were direct hits and the third spiraled into the ground maneuvering for an advantage against Stewart. But what distinguishes Stewart even more than this accomplishment happened in 1949 at the national Top Gun competition. Stewart along with Alva Temple and James H Harvey III competed in this event representing the 332nd Fighter Group. These three black pilots swept the competition. "A warm feeling of justification finally arrived. The country recognizing that African-Americans can perform just as well as anyone else," says Stewart. Despite winning the competition, Stewart had to fight to be recognized because he later found out they were never officially listed as the winner in the Air Force Almanac. Furthermore and, possibly to avoid any further embarrassment, the Air Force broke up the members of the 332nd and transferred the members to many different units. "It wasn't until many years later the question was brought up--where is this trophy? The Air Force claimed that the trophy was lost, that we did not know who the winners were. There was a suspicion on the part then of a number of people that maybe this could have been done on purpose or it could have been a conscious omission," says Stewart. The trophy was found in 2004 after a historian searched and discovered it was in a warehouse at Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, OH. The original trophy remains at a museum in Dayton, but a replica trophy resides in the Charles H. Wright Museum of African-American history, Detroit. From his life’s experiences, Stewart added, "Don't give up, persevere. Don't let failure or hurt feelings gnaw at you and waste your energy." He remained in the Air Force and retired as a Lt. Colonel. In this painting, Stewart has just returned from his mission and is indicating his three kills that day. |

Walter PalmerOne of my paintings honoring the Tuskegee Airmen is of Walter Palmer standing by his P-51C Mustang “Duchess II”. On July 18, 1944, Walter shot down a Messerschmitt 109 with this Mustang. He flew P-39's, P-40's, P-47's and P-51's with the 100th Fighter Squadron, 332nd Fighter Group completing 158 combat missions with over 400 combat hours flying time. Walter served with the USAAF from September 1942 to July 1945. |