History of the Flying Tigers

In the summer of 1941, months before America was drawn into World War II by the attack on Pearl Harbor, a small group of American military pilots was secretly being recruited to augment China's Air Force. At the head of this effort was a crusty, retired World War I Army Air Corps fighter pilot who had been hired by China to strengthen the Chinese Air Force. Because America was not at war with Japan, great care was taken to avoid bringing into question this nation's token neutrality. As a result, these volunteer pilots were required to resign their commissions with the US military, travel to China as civilians and enlist in the Chinese Air Force. These roughly 100 pilots and 200 support crew were officials known as "The First American Volunteer Group" or AVG. After their first combat on December 18, 1941, where they were highly outnumbered and very successful, a journalist wrote in his column, "they flew like tigers . . ." From that time on, they became known as the "Flying Tigers." The Flying Tigers were disbanded and replaced by the US military seven months later on July 4, 1942, but during the intervening seven month period, they racked up one of the finest air combat records in history. This brief history of the AVG is told by one of their pilots, RT Smith, recruited from the US Army Air Corps. This is the story from which legends are made. History of the American Volunteer Group by RT Smith (1918-1995)Japan had attacked China in the late 1930s, and by the end of 1940 had captured vast land areas of China as well as her seaports. Millions of Chinese, both military and civilian, had been slaughtered by the Japanese Army and its Air force. The Chinese Air force, with its handful of obsolete planes and poorly-trained pilots, was never a match for the Japanese and by 1940 had nearly ceased to exist. That the Chinese were able to put up even token resistance in the air was due to the fact that Chiang Kai-shek had hired a retired Air Corps Captain names Claire Chennault as his Air Force advisor. Chennault, a former Air Corps pursuit pilot, had been retired due to partial deafness, but was considered by many of his peers to be a master tactician. Once in china, he discovered a situation that seemed hopeless, but immediately took steps to improve training and obtain planes that could compete with the Japanese. For a number of reasons, and through no fault of his own, his efforts met with little success. By the end of 1940 it appeared that China would inevitably lose the struggle. With Japan controlling the seaports and blockading the entire coast, vital military supplies could no longer be brought in from countries friendly to her cause, including the United States. The only lifeline for supply that remained was the Burma Road, a tortuous unpaved passage hacked through the most rugged mountainous terrain in the world and stretching for hundreds of miles from northern Burma to Kunming in southwestern China. From the seaport of Rangoon, supplies could be shipped by rail to northern Burma, then transferred to trucks for the perilous journey on to Kunming. And now even that critical lifeline was threatened with the Japanese moving unopposed into Indo-China and establishing air bases from which their bombers could attack the truck convoys on the Burma road itself.

This was the situation when, in early 1941, Chennault and a handful of prominent Chinese officials visited Washington D.C. and met with counterparts from the U.S. Government to discuss what could be done to keep china from falling to the Japanese. The plan that evolved called for the purchase by the China Defense Supplies Agency of 100 modern fighter planes from the United States. To fly the planes, 100 military pilots now on active duty with the US Navy, Air Corps or Marine Corps would be allowed to resign their commissions in order to volunteer to fly and fight on behalf of China. Another two hundred volunteers from the enlisted ranks would be recruited and hired as ground-support personnel; crew-chiefs, armorers, propeller specialists, communications, administrative and medical staff. This group would be called the First American Volunteer Group, and it was hoped that other groups, including bombers, would follow.* The plan proposed by Chennault and the Chinese was met by stiff resistance in some quarters, and wholehearted support in others. Since the United States was not at war with anybody at that time, many feared that such plan would provoke the Japanese unnecessarily. Others felt it might be the last hope for saving China. Fortunately for China, the plan received the blessing of then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the wheels were set in motion.

It was decided that China would be allowed to purchase 100 P-40B "Tomahawk" fighter planes originally destined to go to Great Britain. The British would instead receive 100 later-model P-40E "Kittyhawks" with improved armament and performance. A company called Central Aircraft Manufacturing Corporation (CAMCO) was set up with offices in New York city to handle procurement and administrative duties in addition to recruiting the necessary personnel. In the late springs and early summer of 1941 four or five recruiters, all former military men well-known to Chennault, visited Army Air Corps, Navy and Marine Corps air bases. Pilots and ground personnel were gathered in separate groups and briefed on the plan. It called for volunteers to resign from their current military commitments and sign a contract calling for one year's employment in their military specialty as members of the Chinese Air Force. The primary mission would be defense of the Burma Road, the duty would be hazardous, and inevitably there would be casualties. The pay-scale would amount to more than twice the amount currently being paid by the US Military, with most of the pilots to receive $600 per month. Transportation to and from China would be provided by CAMCO.

In the beginning, the recruiters had hoped that they would be able to pick and choose only those pilots with considerable experience, preferable with three or four hundred hours in fighter type aircraft and proficient in aerial gunnery. They soon learned, however, that not nearly enough pilots with those qualifications were ready to volunteer for such an assignment. The same proved to be the case, perhaps to a lesser degree, from among the enlisted ranks. In any case, the recruiters were forced to lower their sights a good deal, and by mid-summer of 1941 had signed up a hundred pilots whose experience, with some exceptions, was a far cry from what was originally planned. My own case was not atypical: I was a Basic Flight Instructor at Randolph field, the Air Corps Training Center near San Antonio, Texas. I had never flown a fighter plane, had received no gunnery training of any kind, and indeed had never even seen a P-40. So just who were these guys? Well, we wound up with about fifty former Navy pilots, about thirty-five ex Air Corps, and about fifteen from the Marines. Of these numbers, about one out of three had had any significant training and experience in fighter planes and aerial gunnery. The rest were the damndest assortment you can imagine; from the Navy, former pilots of dive-bombers, torpedo-bombers and flying boats. And from the Air Corps there were some who'd been flying bombers, or ferrying aircraft from US factories to Canada and a handful of instructors like myself. For sure, this was not a bunch that anyone in their right mind would have labeled "Flying Tigers."

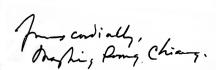

<--- "Blood Chit" sewn onto the backs of AVG flight jackets. In the event the pilot is shot down, this advised natives that this pilot was an American fighting for China.And why did we volunteer for such dangerous duty when we could have remained safe and comfortable in a peacetime military environment? Obviously, there is no one answer to such a question. A very few may have been enticed by a bigger paycheck, but not many would willingly stick their necks out to that extent simply for a few extra dollars. Many of us, at least to a degree, were idealists who knew we would be fighting for a just cause. Most wanted to prove to themselves that they had both the courage and ability to engage an enemy in battle and beat him. Some felt they were in a rut, dissatisfied with their military assignments in the US, wanting to be fighter pilots instead of being restricted to the limited horizons of flying bombers or training planes. So there were a number of reasons, and I believe that a combination of these prompted most of us to sign up with the AVG. There was one other reason, however, that was common to us all, and that was a strong thirst for adventure in faraway places. While we might be regarded as Soldiers of Fortune or Mercenaries by others, in our own minds we were simply adventurers. This above all else made us a very close-knit group, pilots and ground personnel alike, and engendered a spirit that was to sustain us through the many difficult and dangerous months ahead. All of us were to become familiar with what it meant to be on a slow boat to China, although our first destination was to be Rangoon, Burma. We traveled in manageable groups on four or five different ships embarking from San Francisco throughout the summer of 1941. The trip took from five to seven weeks time with three or four stops along the way. The first contingent arrived about the first of September and immediately set about assembling the P-40s that had been shipped to Rangoon in huge crates. The last contingent arrived in mid-November at the little used air strip that the British RAF had loaned to us for use as a training base. This base was near Toungoo, Burma, about 170 miles north of Rangoon. Chennault and his small staff organized the group into three pursuit squadrons, each to have 33 planes and pilots, and a severely limited number of ground crew personnel to service and maintain them. The plan was to train the group in Burma until it had become an efficient and capable fighting unit, then move to what would be our main base of operations in Kunming, China, by the end of the year. Our training schedule was hampered by monsoon rains for many weeks, and as might be expected, many of the pilots had difficulty in transitioning into the P-40, which proved to be trickier to fly than what they'd been used to. There were many accidents, a dozen or so planes wrecked beyond repair, and three pilots killed. Add to this the primitive and rugged living conditions that prevailed, and you can almost understand why several pilots and ground crewmen resigned and headed back to the States by the end of November. There was no way to hold them, the contract they signed being unenforceable, and for that matter, Chennault was glad to weed out the malcontents before going into battle.

<-- RT in front of #68 Chuck Older's P-40So this was the situation when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 (December 8 in Burma). Our group went on full alert immediately, of course, spurred by reports that the Japanese were moving into neighboring Thailand. A few days later Chennault ordered the 3rd squadron (Hell's Angels), of which I was a pilot, to Rangoon to help defend that vital seaport. A week or so later the other two squadrons were moved to Kunming, and just a couple of days after their arrival they engaged in the first combat action of the AVG. Elements of the 1st and 2nd squadrons engaged a force of IO twin-engined Japanese bombers enroute to their target, Kunming. Six of the bombers were shot down, and the others severely damaged as they high-tailed it back toward their base in Indo-China. According to later reports, only one of the bombers made it back safely. This action took place on December 20th, 1941, less than two weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The 3rd squadron, stewing in Rangoon, didn't have long to wait for its baptism of fire. On Dec. 23rd, and again on Christmas Day, the Japanese Air Force appeared in awesome numbers; some 60 twin-engine bombers and 30 fighters came swarming in from bases in Thailand. We met them with 14 P-40s, all we had available, and in the two encounters, shot down a total of 35 Jap bombers and fighters, damaged many more, with a loss of five P-40s and two pilots. This, my friends, was the ultimate in on-the-job training! What followed from that point on throughout Burma and China until July of 1942 has been well-documented, and I believe our record speaks for itself. And very early in the game the Chinese people, and the press, began referring to us as the Flying Tigers. Our victories over the Japanese during those early weeks and months after Pearl Harbor were among the few things that the United States could be proud of or boast about. We were hailed as heroes even more by the Chinese people than the press, and of course we loved every minute of it. What had started as a rag-tag bunch of wild adventurers had turned into a dedicated and efficient fighting machine. Some of those in the US Government, particularly in the military, who had predicted that we would not last three weeks in combat were forced to eat their words. Chennault, unheard of except by a handful of people, was suddenly acclaimed as a genius for his tactical abilities. He was justifiably proud, of course, but was always the first to agree that it was his Flying Tigers - the AVG, pilots and ground personnel alike - that made him famous, not the other way around.

It was in the spring of 1942 that Roy Williams of the Walt Disney Studios in Hollywood designed what was to become our group insignia. It consisted of a winged-tiger flying through a large V for Victory. It was both unique and beautiful, and we loved it. In due time, we received a supply of large decals of this insignia and many of us applied them to the side of the fuselage of our planes. Once the United States was forced to declare war following the attack on Pearl Harbor, we of the AVG knew that our days were numbered. We knew that the US would eventually have to send military units, most likely in the form of several fighter and bomber squadrons, to come to the aid of China. Rumor had it that the AVG would be inducted, en masse, into the US Army air Corps within a matter of weeks. The reasoning, of course, was that an organization of so-called "civilians" such as the AVG could not co-exits with military organizations. This was probably true, but it was equally true that the US had neither the manpower nor equipment readily available to supplant our efforts immediately. So it was decided that the AVG would continue to function as originally intended until July 4, 1942, at which time the first contingents of US Air Corps planes and personnel would take over.

It was also decided that Chennault would remain in command, and in the spring of '42 he was re-commissioned as a Brigadier General in the Army Air Corps. Pilots and ground personnel of the AVG were offered the option of being inducted, with suitable rank, into the Air Corps on July 4th or returning to the United States. A Brigadier General Bissell briefed us in Kunming on this proposition, but made it more of a threat than an offer, promising that if we returned to the States, we'd be met at the dock by our draft boards, and refusing to grant us a couple of weeks leave if we stayed. By this time, after six months of constant combat, we were pretty well exhausted, both mentally and physically, and needed a rest. We'd had many victories and were proud of our accomplishments, but the price had been high. Twenty-two of our pilots had paid with their lives, either in accidents or in combat. Three more had been shot down in enemy territory and were now prisoners of war. One of our crew-chiefs had been killed in a bombing attack on one of our little airstrips in Burma. We had lost many planes and received only a handful of replacements, practically no spare parts. By July we were down to about twenty war-weary planes capable of combat, and perhaps twice that number of relatively healthy pilots. We all felt that it was high time the US Military should step in with fresh planes and pilots and the resources to back them up properly.

Charles Older & RT Smith -->And so, while most of us had every intention of going back into military service, few were eager to accept induction then and there. Only five pilots decided to accept commissions and remain, along with a couple of dozen ground personnel who agreed to being inducted. The rest of us would be free to leave early in July and return to the States as best we could. The Air corps showed its "appreciation" by refusing to provide air transportation beyond a point in northeastern India despite the fact that there was space available on many a transport plane of the Ferry Command heading toward the middle-east, Africa and eventually the United States. As a result, most of us were forced to make the long and hazardous journey by boat and at our own expense. The immediate successors to the Flying Tigers was an Air Corps unit called the China Air Task Force (CATF), which had ben part of the 10th Air force with headquarters in India. The CATF included the 23rd fighter Group, composed of three squadrons of P-40Es, and a squadron of B-25 bombers. Chennault was named to command the CATF, and the first Commander of the 23rd Fighter Group was Colonel Robert L. Scott [author of "God is My Co-Pilot"], who had flown a couple of "guest" missions with the AVG in the spring. The three squadrons of the 23rd were placed under the command of three of the five former Flying Tigers who had been commissioned when the AVG was disbanded. Now majors, they were Tex Hill, Frank Schiel and Ed Rector - all with outstanding combat records. The following letter was in response to RT Smith sending Madame Chiang a copy of the picture at the top of this page.

The 23rd Fighter Group carried on and in short order began what would prove to be an enviable record of its own until the end of the war. The Group adopted, as part of its insignia, a winged-tiger similar to that of the AVG, but members of the group neither thought of nor referred to themselves as Flying Tigers. That distinctive name was willingly conceded to the AVG, at least until many years later. The CATF continued to do an outstanding job for the news few months, but in March of 1943 it was absorbed by the newly activated 14th Air Force in China. Chennault, now a Major General, was named to command the 14th which adopted still another version of a winged-tiger as its official insignia. Over the next many months the 14th AF grew into a formidable force. By war's end, it included additional fighter groups equipped with P38s, P47s and P-51s as well as the trusty P-40s, plus bombardment groups with B-24s as well as additional B-25s, transports, etc. Manpower was estimated to be approximately 20,000 at its peak. And again it might be worth noting that all those thousands of 14th Air force people, as was the case with the 23rd fighter Group earlier, were justifiably proud of their own accomplishments and very few, if any, thought or referred to themselves at that time as Flying Tigers. Meanwhile, most of us who had chosen to return to the United States traveled across India by train to Bombay or Karachi, and after considerable delay, managed to book passage on an American troop transport. We were 30 days enroute to New York, with a brief stop in Capetown, South Africa, before the long haul through the submarine infested Atlantic Ocean. Instead of representatives of our draft boards, we were met at the dock upon arrival by news reporters and photographers, and given a royal welcome. It was good to be back! In late 1940, a delegation from Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek was in the United States to buy airplanes. A demonstration of the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk was scheduled in Washington for the Chinese visitors and their American advisor, Claire L. Chennault. The pilot for the demonstration was 2nd Lt. John R. Alison. As Chennault would later recall in his book, Way of a Fighter, Alison "got more out of that P-40 in his five-minute demonstration than anybody I ever saw before or after... "When he landed, the Chinese pointed at the P-40 and smiled, 'We need 100 of these.' 'No,' I said, pointing to Alison, 'you need 100 of these.'" |